Navigating Disruption: 4 Case Studies in Digital Transformation Strategy

Let’s cut through the marketing speak.

Overuse has obscured the meaning of terms like “disruption” and “digital transformation,” making it hard to clarify the threat that disruption actually poses, and identify the strategies of companies that make through to the other side and thrive in the new reality.

Even if the terminology feels abstract, the effects are real. We’re talking about the life and death of companies and industries.

The ‘automation first’ era is upon us, and, as in the mainframe, personal computer, and mobile technology eras that preceded automation first, businesses that can’t adapt will lag behind.

Businesses and employees are already using software robots to increase efficiency, generate greater returns, and free employees from tedious tasks. It’s easy to envision a time in the future when every human will have a software robot of their own at their disposal—a robot for every person.

Companies that are thriving in this automation first era have developed digital transformation strategies that prioritize a change in mindset. That shift means, first and foremost, that if something can be automated, it should be automated.

The best way to develop a digital transformation strategy is to learn by example. In this article, I’ll go over four companies that succeeded or failed against the threat of disruption. None of them failed to see the future, but only some managed to successfully adapt to it.

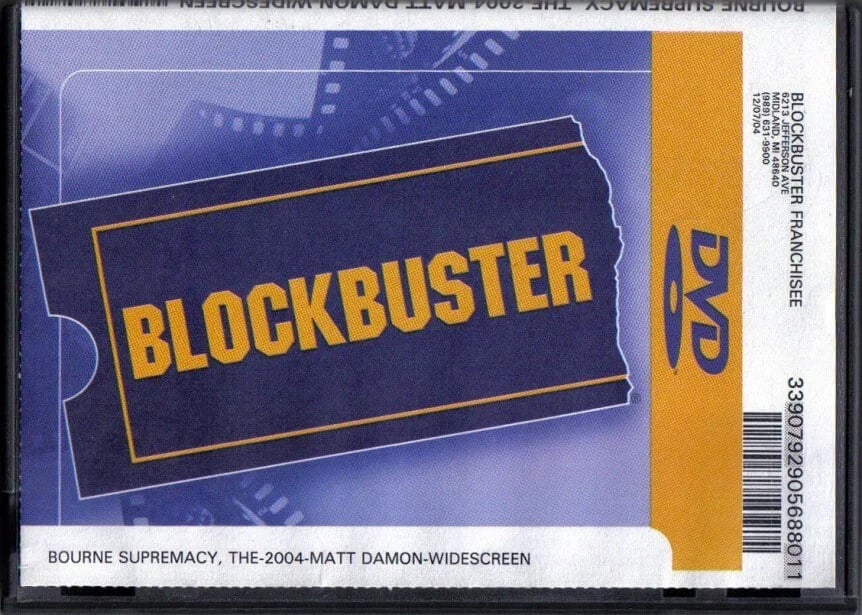

1. Blockbuster: How a retail juggernaut fell behind its customers

We often talk about companies that failed to navigate disruption in terms of vision. In many classic cases of disruption, however, companies had plenty of time to recognize the threat they faced; they just failed to act.

Blockbuster is infamous for its failure to transform. The story, as it tends to be told, focuses on former Blockbuster CEO John Antioco turning down Reed Hastings’s offer to acquire a fledgling Netflix in 2000.

Netflix eventually became the giant we know today, Antioco was relieved as CEO, and Blockbuster went bankrupt.

The lessons aren’t in Antioco’s mistake but in the decisions that followed it.

Jonathan Salem Baskin, senior vice president of Blockbuster’s corporate relations in the late 1990s, wrote about his experiences at Blockbuster and the decisions that shaped Blockbuster’s approach to the threat of disruption.

A video-rental business might seem quaint now, but, at the time, the business model was highly profitable. Movie studios priced VCR tapes at nearly $100, pushing them outside the price range that an average consumer could afford. Seeing the opportunity, rental stores purchased the tapes and rented them cheaply.

Everyone won—especially the rental stores. Once a store rented a tape enough times to clear the initial investment, every subsequent rental was pure profit.

This model only needed to rely on effective logistics. Acquiring more stores gave Blockbuster more supply and more data to fuel selections. Its success shaped an understanding of their customer that disruption eventually unraveled.

As the internet-era emerged, Blockbuster’s grip on movie rentals faced a major challenge from a new internet-first company – Netflix. Customers began signing up to choose movies online, and receive them in the mail. Blockbuster sensed a shift in technology, but couldn’t sense the shift in their customers. Instead, they added candy and toys to their stores, upping profit margins with impulse buys while waiting for the environment that sustained their business model to recover.

Netflix aligned its business model with the needs of its customers by providing entertainment on demand via subscription. Blockbuster’s business model was instead tied to late fees, introducing friction when a customer wanted to rent.

When Blockbuster was the only option, customers endured the friction. When Netflix entered the market, that disruption became unbearable.

Instead of addressing its core problems, Blockbuster distracted itself by playing catch-up and taking big, poorly planned risks.

Blockbuster signed an exclusive deal with Enron Broadband Services to provide video-on-demand in 2000 but had to tear up the contract after nine months due to Enron’s scandals.

Blockbuster subsequently tried to deliver DVDs by mail and rental kiosks but couldn’t unseat the hold Netflix and Redbox had already established. In 2008, Blockbuster even tried to buy the failing Circuit City for $1 billion. Circuit City went bankrupt later that year.

Even when Blockbuster directly addressed Netflix’s disruptive service, Blockbuster’s assumptions about its customers proved to be an Achille's heel. Blockbuster on Demand had newer content than Netflix, but they charged consumers on a title-by-title basis—as much as $3.99 per title. Blockbuster couldn’t figure out how to provide a frictionless experience.

The company filed for bankruptcy in 2010.

Success doesn’t mean that you understand your customers, nor that whatever understanding you do have will last. Customers came to Blockbuster not out of brand loyalty or a desire to experience its stores but as a way to get entertainment.

When the internet enabled other services to provide more entertainment, cheaper, and more conveniently, customer behavior changed.

By not understanding the problem that their solution temporarily solved, Blockbuster was unable to adapt to an internet-first company when it needed to.

2. Microsoft: Creating new values for renewed success

Disruption is more a pattern than an event. When one company takes the place of another, it’s likely only a matter of time before another company arrives to unsettle the industry again. If you’re not humble about your success, your victory will set up your eventual loss.

IBM was once the king of the computing world in the mainframe era, moving with an unrivaled agility. But in 1980, IBM realized the potential of the fledgling personal computer industry and rushed to catch up by inking a deal with a small, unknown company: Microsoft.

IBM paid Microsoft for the right to use their operating system (OS) but—crucially—allowed Microsoft to keep licensing that OS to other companies. By focusing on personal computers, IBM missed a more important shift.

The point of leverage in the computing industry was moving from hardware manufacturing to the operating systems that linked software and hardware. Microsoft was ready to enter the door IBM had opened.

Over the following decades, Microsoft built its dominance on Windows. They understood that the graphical user interface (GUI) was the key to broad PC adoption, and partnered with manufacturers to place their software on most of the PCs that shipped.

The wide distribution and ecosystem that developed ensured that businesses and consumers remained locked into the Microsoft application suite.

This strategy built a massively successful company, one that completely transformed the computer and software industries.

As we saw with Blockbuster, however, no degree of prior success will guarantee your survival once technological and consumer trends start moving in different directions.

Ben Thompson, a technology writer, argues that three trends eroded the foundation Microsoft relied on:

The rise of the Internet, web applications, and software as a service (SaaS) reduced application lock-in, enabling people to reach outside the Microsoft ecosystem.

PC hardware and design reached a level of quality that was high enough to lengthen the upgrade cycle, reducing the number of new purchases.

Smartphones captured consumer needs that the PC couldn’t.

Despite these trends pointing away from Windows and OS centricity, former CEO Steve Ballmer publicly recommitted to a Windows-first philosophy in 2013, stating, “By deploying our smart-cloud assets across a range of devices, [Microsoft] can make Windows devices once again the devices to own.”

So far, this appears to be a classic example of the disruption pattern about to repeat. A company rises to glory, refuses to face new trends, and eventually collapses.

In early 2014, however, Ballmer was replaced by Satya Nadella, who steered Microsoft away from the edge it was likely heading toward.

When Nadella took over as CEO, Microsoft’s stock closed at $36.35; by late 2018, it was trading above $113 per share. This dramatic course correction carries lessons for any company planning a digital transformation strategy.

When Nadella came in, he changed the entire culture. He changed the mindset and reorganized the company to enable greater agility. To sanctify Microsoft’s new future, Nadella made Microsoft Office available on the iPad—something the old guard would never have agreed to. He understood the PC era was over and something new had emerged.

Nadella had a vision and a future-oriented digital transformation strategy that previous leaders lacked. Nadella pivoted from “Windows-first” to “Windows-and.”

Compare Ballmer’s message emphasizing Windows with Nadella’s first strategy memo only months after taking over:

“At our core, Microsoft is the productivity and platform company for the mobile-first and cloud-first world. We will reinvent productivity to empower every person and every organization on the planet to do more and achieve more.”

By shifting from the assumption that Windows had to be the sun around which all computing experiences orbited, Microsoft was able to better identify, track, and serve evolving customer needs. With productivity as their new mission, they were free to pursue different goals and strategies to fulfill that mission.

As alluded to before, this renewed strategy has led Microsoft to more partnerships. A company previously focused on establishing and then defending closed ecosystems has now formed substantial relationships with would-be competitors, including Dropbox, Red Hat, and Amazon—including an appearance from Nadella at a Salesforce conference.

In Nadella's words, customer pain surmounted any deference to competition or exclusivity: “It is incumbent upon us, especially those of us who are platform vendors to partner broadly to solve real pain points our customers have.”

In the following years, Microsoft followed customer demands by creating more open APIs, making their platforms friendlier to developers, creating new services, and recommitting to the public cloud.

Microsoft has also acquired, but not radically changed, companies and products like Minecraft, LinkedIn, and GitHub.

Microsoft supported this business-model shift with a culture shift from destructive, internal competition to an empowering growth mindset that embraced learning from risks.

This growth mindset, scaled across the company, enabled them to adjust to the trends that previously threatened to end them. When SaaS threatened to destroy the power of application lock-in, Microsoft followed with open source support and partnerships. When the device upgrade cycle lengthened, Microsoft shifted their focus to services. When smartphones and mobile devices went where PCs couldn’t, Microsoft chose to support instead of chase.

Microsoft’s digital transformation strategy was one of humility—recognizing that success doesn’t always come from dominance.

Instead, Microsoft pursued customer need first and foremost and found a place for itself supporting customers at various points in their lives, from the office to the home and from devices outside Microsoft to services within.

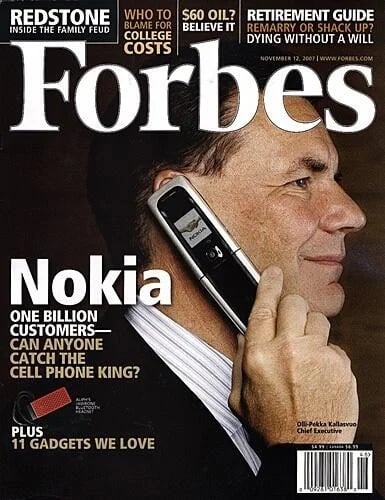

3. Nokia: How a former innovator trapped itself in its own success

Nokia had a lot of success. Innovation and adaptability were never foreign ideas.

Even companies that have built their profits on innovation will face disruption if they’re not willing to refresh their approach.

Nokia started as a paper mill in the late 1800s, eventually merging several jointly owned businesses to form the Nokia Corporation in 1967. Nokia laid out its future in the late 1970s and early 1980s when it launched the first international cellular system. Nokia released some of the first mobile phones, though their cumbersome, heavy weight made mobility a little dubious.

By the late 1990s, Nokia was the world’s top cell phone provider.

Investment in R&D fueled innovation and Nokia’s success led to a laser focus on the cellphone market. They were even the first to develop a touch screen, internet-enabled phone. Where could it go wrong?

Nokia’s failure was written by its success.

Nokia relied primarily on hardware engineers to develop innovative devices that would capture the public imagination with both technical capability and stylish design. By 2007, Nokia dominated; it hoarded over half of all the profits in the mobile-phone industry.

Predicting its failure would have been a bold claim, and people hailed its market power.

That dominance, however, wasn’t due to smartphones, so the rise of this new technology appeared to be a risk rather than an opportunity. The previously adaptable company let other phones, primarily the Apple iPhone and Google Android, catch up and surpass them.

Wedded to its previous path to success, Nokia believed their hardware design would keep users loyal as Nokia found its way in the, by then, rapidly growing smartphone market. Instead, users fled Nokia to phones with better software, seeking improved user experiences.

Prior success doesn’t predict future success.

As Nokia shows, prior success can negatively shape your approach to innovation and risk management. Nokia overestimated the risk of shifting to smartphones but underestimated the risk of disruption.

The very approach that made Nokia dominant also cleared the way for defeat. Without the willingness to depart from success, even the biggest companies will eventually fall.

4. Unilever: How a giant rebuilt itself for speed

Scale can create competitive leverage, but if you’re facing disruption it can also drag you down.

Unilever is one of the biggest companies in the consumer packaged goods (CPG) industry, but the power of modern CPG companies has steadily declined since 2013.

Unilever started selling margarine and soap in the early 1900s. Over the following decades, they scaled to selling a multitude of products made from oils and fats. The company also acquired companies like Lipton, Ben & Jerry’s, and Dollar Shave Club.

After 2010, Unilever started pulling away from its declining food business and moved toward health and beauty.

This shift kept the company going, but its scale meant agility would be a challenge.

Traditionally, enterprises buy customer data from market-research firms, but Unilever chose to build its own database. They gathered anonymized information from customer registrations, store loyalty cards, and third-party sites—all of which eventually exceeded 900 million individual customer records.

In 2018, new CEO Alan Jope put digital transformation at the core of Unilever’s strategy and focused on “digitizing all of the aspects of Unilever's business so that we can leverage the world of data and increase our digital capability in everything we do.”

Unilever had found a point of leverage.

With a massive amount of data backing their digital-transformation and product-development strategies, Unilever has been able to spend less and sell more.

When they were selling Baby Dove in India, for example, their data enabled targeted advertisements that cost one-fifth the normal price for the same brand-awareness impact. Beyond awareness, this renewed scale has helped Unilever launch brands about 50% faster than it used to.

We used to think in years, quarters, months. As soon as you start digitizing your company, you start thinking in quarters, months, and weeks.

Peter Ter Kulve, Chief Digital Officer, Unilever

Unilever matches the scale of its data with the scale of small, nimble teams. “Digital hubs” around the world gather analysts together to study consumer traits, segment the traits into hundreds of categories, and build content to serve them. These teams are made even more agile with the support of an extensive artificial intelligence (AI) system that can help predict upcoming trends.

Disruption can destroy companies and industries because it enables new structures that can outcompete yours, whether that be new ways of connecting to customers, new business models, or new ways to design products.

Unilever is a model example because they have embraced the danger and reorganized its company to face the threat.

When Unilever realized that many of the processes in its service lines, including supply-chain management and master data management, were slowing it down, it looked to transform those processes with Robotic Process Automation (RPA).

Adaptability isn’t a static goal. Unilever’s focus on efficiency has involved transformation in product development and process automation. New technologies will continually call on businesses to find different ways to improve agility.

Disruption won’t end; neither should your willingness to rebuild.

Lessons from the history of digital transformation

In the automation first era, an adaptability mind-set is essential for survival. Disruption doesn’t necessarily mean your core product has lost its value. It means the relationships between you and your customers are shifting, and the infrastructure necessary to build and maintain those relationships is also changing.

The companies that have so far survived disruption were willing to invest in digital transformation and change the mindset of the company. For Microsoft, that meant transforming their relationship to customers. For Unilever, that meant transforming their approach to scale.

Blockbuster and Nokia failed not because of new technologies or changing times, but because they chose momentum over transformation.

Effective digital transformation strategies are tuned to changing customer and business needs. In the automation first era, you’ll be able to fulfill potential that has, thus far, remained untapped.

How many problems could you solve if software robots freed your employees from repetitive labor?

How many more customers could you help if each employee had a robot at their disposal?

What could you do with the scalable power of robots on your side?

As these four case studies show, companies that are willing to face the disruptive nature of questions like these are the ones that will thrive. The automation first era is here, and now is your chance to transform.

Chief Marketing Officer (CMO), Ada

Get articles from automation experts in your inbox

SubscribeGet articles from automation experts in your inbox

Sign up today and we'll email you the newest articles every week.

Thank you for subscribing!

Thank you for subscribing! Each week, we'll send the best automation blog posts straight to your inbox.