RPA and the ROI Conundrum

Many clients are looking for cookie-cutter answers concerning the return on investment (ROI) of a robotic process automation (RPA) project. Of course we, as vendors, would be happy to oblige with simplistic and flattering answers. With the annual cost of robot license being — depending on the location and the job profile—2 to 15 times lower than that of a full-time equivalent (FTE) while theoretically covering the work of five FTEs, justifying the ROI of an RPA deployment seems easy, right?

Well, experience shows that it might not be that simple. First, it is essential to distinguish whether one wants to build the ROI of a specific process, or of an entire program. Many companies start with the first option in the early days of their RPA deployments, during the pilot phase, when they automate only a handful of processes. By choosing the “low-hanging fruit,” (the first processes to be automated) they identify the staff hours that can be saved and thus assess the benefits relatively quickly. But, any organization will sooner rather than later run out of these easy use cases and will need to move into building an ROI for the entire RPA program. At that point, the benefits can no longer be pinged to a specific process but rather to a portfolio of processes.

My recommendation would be to build a business case for your RPA program over a 24 to 36 month period. To do so, you would need to identify the benefits on the one hand, and all the related costs on the other.

Let’s start with the benefits. The most straightforward benefit to measure is the time that the automation will save.

RPA benefits

So by extrapolating from the pilot results and by doing a high-level assessment of the categories of processes that will be automated, the potential time to be saved can be hypothesized (typically between 30 to 70%). Once the time savings have been estimated, based on the category of employees whose work will be automated and the location of the FTEs, a fully loaded average hourly cost of these resources can be calculated. It is essential for these hourly costs to be fully loaded to include benefits, use of facilities/IT, future training costs, turnover rates, future salary increase and so on.

Automation provides other benefits as well, most notably the elimination of errors, which can be extremely costly.

Unfortunately, there is no robust and straightforward methodology, and they may vary quite a bit from one process category to another. Rather than trying to pin it down with a time consuming and sophisticated approach, I recommend a more simple way based on a consensus within the company. The idea is to agree qualitatively whether a set of processes has high, medium or low error rates and consequently apply to it a benefit multiplier ranging from 1.1 to 1.3. This approach, while not being wholly accurate, allows nonetheless to pragmatically account for all the other benefits that automation brings beyond time savings.

On the cost side, there are four major categories to consider:

The cost of the automation tool;

The extra cost of infrastructure;

The cost of development;

The cost of monitoring and maintenance.

The cost of the automation tool

This is probably the easiest of all costs to estimate as the automation tool licenses costs are known from the start. The only hypothesis to consider is the ratio of robots used per automated process. While it is safe to start with a 1 for one ratio in the early days, this ratio will improve over time as economies of scale are reached and can probably reach 2.5 to even 3. Of course, this will only apply for vendors that allow dynamic allocation of robots to processes.

The extra cost of infrastructure

As the RPA program advances, companies may have to further invest in IT infrastructure regarding virtual machines, servers, and better test environments. A discussion with the IT department and the technical architects should allow for the proper sizing of these potential extra-costs.

The cost of development

This is the most substantial and the most difficult cost to estimate. It will represent a significant upfront cost and will depend on two main variables: the delivery model chosen by the company and its evolution over time (i.e., insourcing vs. outsourcing) as well as by the complexity of the processes to be automated.

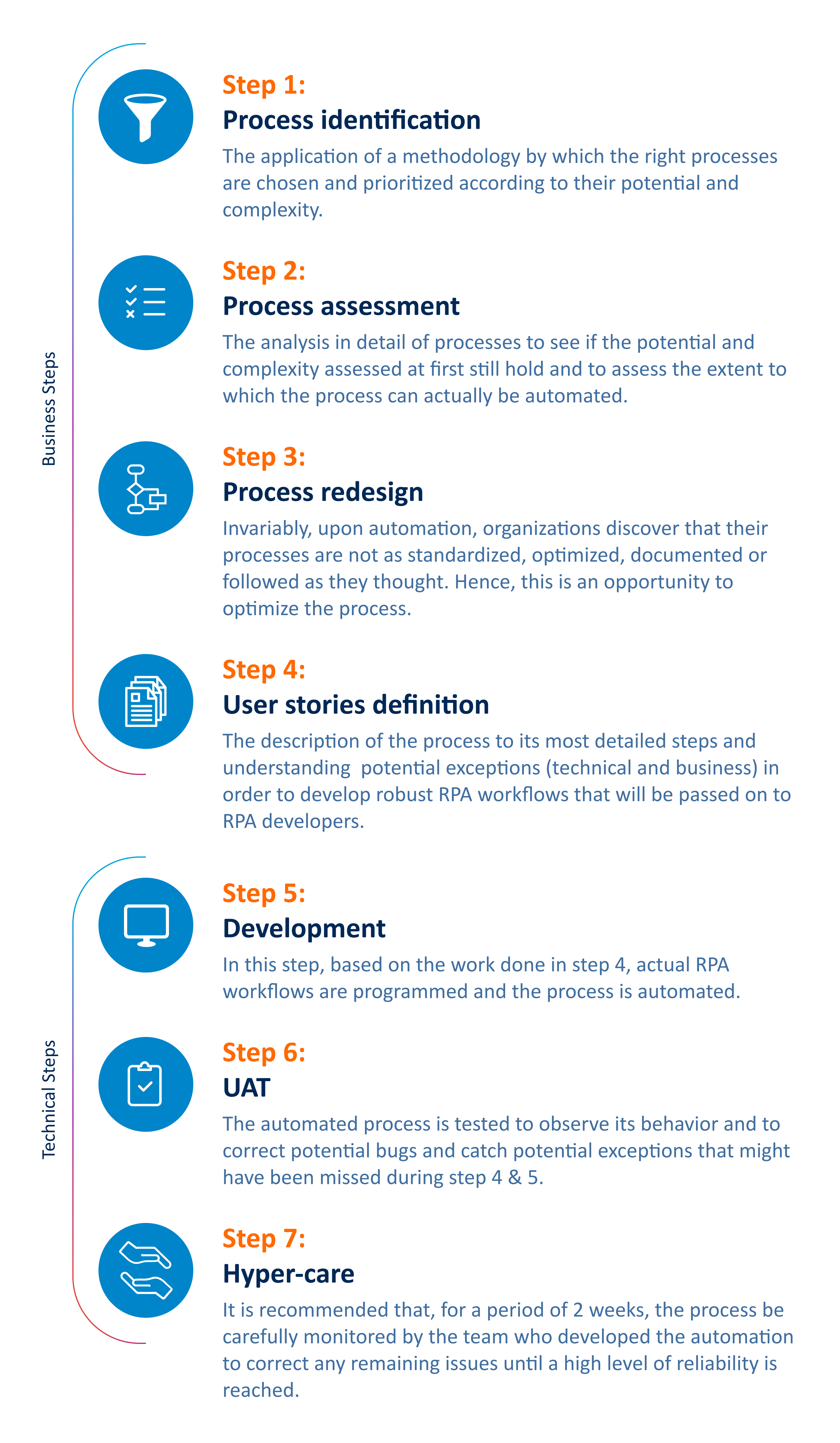

Automating a process requires more or less seven steps, three of which are business related and four of which are more technical, requiring a varied set of skills. The cost of automation will vary on whether a company decides to perform itself a whole or a part of these steps. In addition to that, many companies re-design processes to some extent or have the cost of process redesign already budgeted as part of their continuous improvement program.

If they decide to automate on their own, the upfront cost of development might be higher as they are building up their teams before reaching scale. A robust discussion on the delivery model chosen and its evolution over time will prove to be necessary in building a proper business case.

The second variable is the complexity of the processes being automated. In industry jargon, people may call a “process” a simple task with several steps — for example, an SAP log-in, or they may call a “process” an entire workflow comprised of several tasks — for example, the process of onboarding a new employee. The length and complexity of automating one versus the other will vary tremendously. For instance, going through the six steps of automation can take as little as ten working days or as much as 70 working days, even more.

An answer to this would be to do a high-level assessment to come up with three categories of process complexity: low, medium and high, and attach to each an average development time and cost afterward deciding on the mix either over the years or per department.

Furthermore, as the development teams become more experienced and start making use of reusable components in their development process, it is fair to expect a productivity increase of 30% to 40% after the first year. This notion should be accounted for in the development cost for subsequent months or years.

The cost of monitoring and maintenance

Once a company has developed many robots, it has a de facto digital workforce that needs to be monitored and maintained. As mission-critical processes will start to be automated, monitoring and maintaining robots will become critical.

Maintenance itself can be divided into three broad categories:

Changes in the automation script driven either by business requirements, exceptions in the process that have been overlooked or changes in underlying applications;

Robots stoppage due to IT infrastructure and application issues;

And finally issues related to the RPA tool itself.

While the last form of maintenance is usually included in the subscription-based cost of the automation tool and hence covered by the vendor, the other types of support need to be accounted for.

The cost of maintenance can be variable per robots or automated processes if outsourced, or semi-variable if performed by an internal team. Early in the project, some of it is a cost that is shared with the development effort if it relies on shared resources.

Building the business case of an RPA program is trickier than building it for a couple of processes. Nonetheless, it is a necessary exercise that needs to be carried with some rigor if one wants to engage the CFO and secure proper funding for a multi-year effort.

While several key variables (e.g., time saved estimates, average development effort, the ratio of robots to processes) may vary, the exercise of building an RPA program business case allows for the necessary dialogue with critical stakeholders.

In our experience, while such an RPA program budgeting may not always yield the desired “under a year ROI” depending on the delivery model chosen, it still, in almost all cases, generates impressive ROI within 18 months and beats hands down all other IT projects on this criteria.

President of the Board, UiPath Foundation

Get articles from automation experts in your inbox

SubscribeGet articles from automation experts in your inbox

Sign up today and we'll email you the newest articles every week.

Thank you for subscribing!

Thank you for subscribing! Each week, we'll send the best automation blog posts straight to your inbox.